Variables and Loops Lab

In this lab, we will learn how to make the computer do the same instruction over and over. To get started, let’s talk about how the code we’ve written works in your computer.

The code process

Now that you’ve got some experience running Python programs, here’s a brief overview of what Python does.

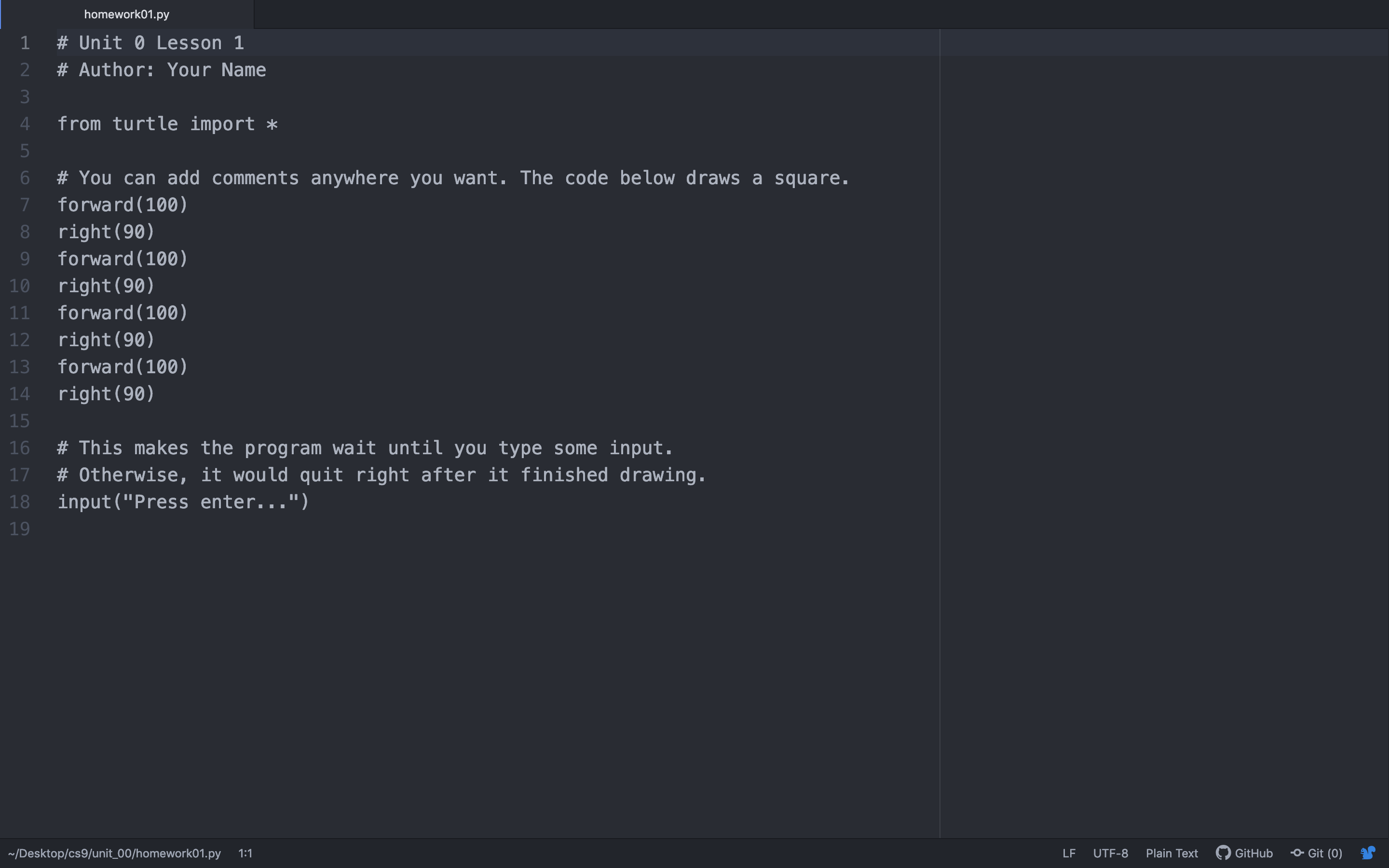

In the first lab, you wrote text into Python files using the text editor Atom.

Text in a text file

This text wasn’t just any text however, it used special terms and syntax from the Python language. This is why

saving your files as .py files is so important - it designates what language to expect inside the file.

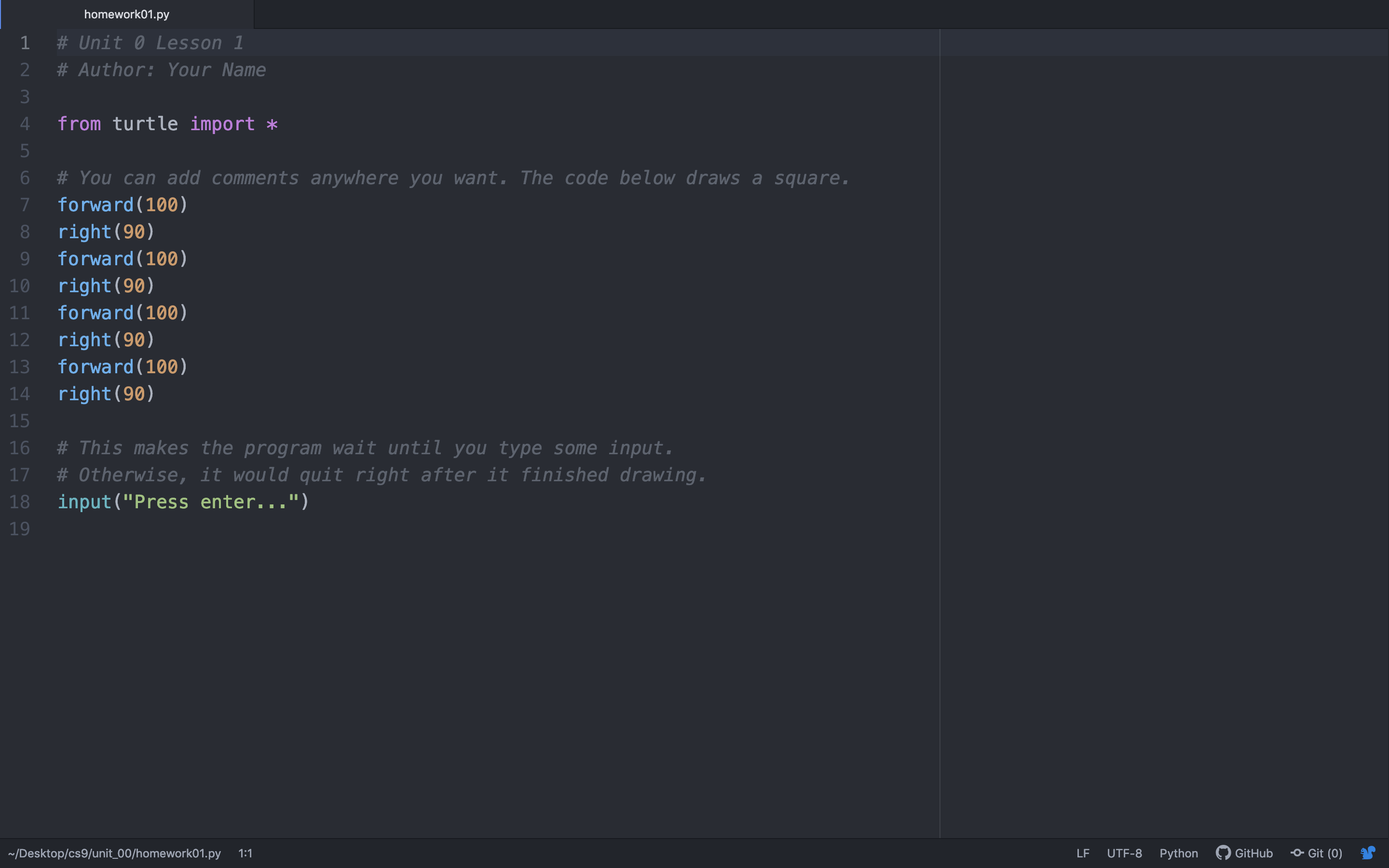

Text interpreted as Python code in a .py file

Just like natural languages like Chinese or English, Python has rules that determine what has meaning and what doesn’t

have meaning in the language. This is known as the syntax of the language. You can write whatever you want in a .py

file, but if it doesn’t follow the rules of python syntax you will get an error when you try to run the program.

Like many natural languages, the order of statements in Python matters. Python (generally) executes statements one-by-one from top to bottom. That’s why these two snippets of code will produce different drawings despite having all the same statements (try it out if you don’t believe):

from turtle import *

forward(100)

right(45)

forward(100)

from turtle import *

forward(100)

forward(100)

right(45)

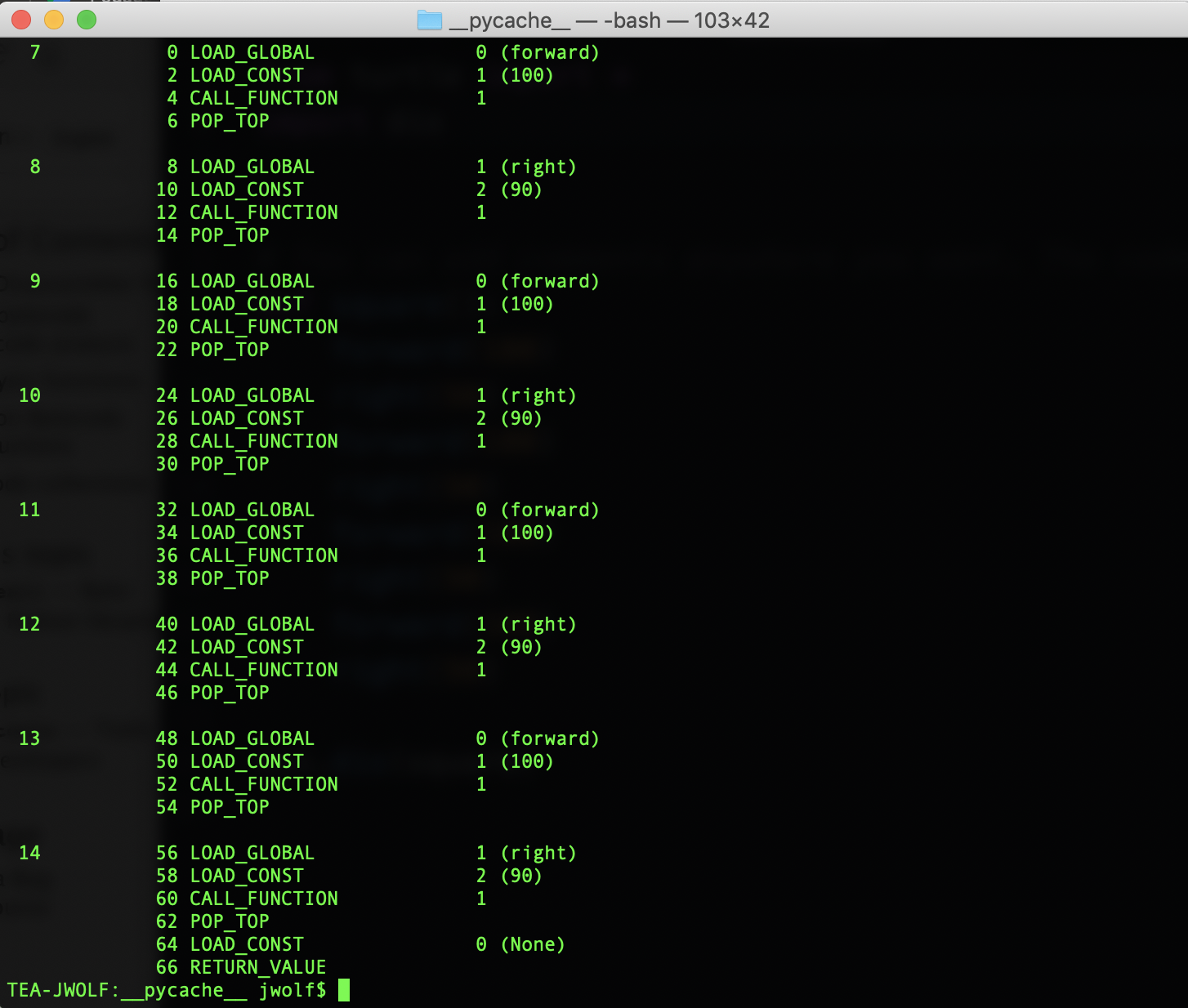

After writing what we want our computers to do with Python syntax, we turn to a program in your computer

called Python3 (which is the program you run when you type python homework01.py in the Terminal). You have

to use correct Python syntax when writing code because Python3 must interpret code and translate it into

something your computer can read, often called machine language.

Code translated to machine language

👾 💬 FYI

Above, we said the Python generally executes statements one-by-one from top to bottom. The word “generally” is necessary here because the Python3 interpreter will sometimes do things in the background to make your code run more efficiently. This might change the way the code is actually executed, but it shouldn’t change the functionality of your code. You can still assume that your code is being executed line-by-line.

Once your code is in machine language, your computer takes over to carry out the instructions you give it. In the case of the drawing assignment, this meant showing a moving turtle drawing lines on your screen.

How your computer acts on the machine code

Python shell

Usually, we write Python code in a file using Atom and then run it using Terminal. There’s another way to run Python, which is really nice for when you just want to mess around or do a quick test.

💻 Open Terminal, navigate

to your computer science directory and type python.

~$ cd Desktop/cs9

~/Desktop/cs9$ python

Python 3.7.3 (default, Mar 27 2019, 09:23:15)

[Clang 10.0.1 (clang-1001.0.46.3)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>>

See how the prompt changed to >>>? That tells you you’re in Python world. You can type Python code here and

it will run. Let’s try it out. Type the following, and make sure you get the same response.

>>> 1+1

2

>>> 123456 + 654321

777777

>>> number = 5

>>> number * number

25

>>> "I am " + "a robot"

'I am a robot'

>>> exit()

~/Desktop/cs9$

Once you exit the Python shell, all your work is lost. So it’s not a good way to do serious work, but it works great as a fancy calculator.

>>> 1+1

2

>>> 123456 + 654321

777777

✅ CHECKPOINT:

Answer the following check-in questions on your group’s Google doc before moving on:

- What does Python3 (the software) do?

- When adding, subtracting, multiplying, and dividing numbers in Python, what is the order of operations? (Use the Python shell to test!)

Variables

One of the most powerful tools of programming is the variable: a storage container for information in your programs.

You are probably familiar with variables in math. (“Solve for x: 2x + 4 = 3x”) In math problems, the goal

is often to figure out the secret value of a variable. Once you figure it out, the problem is finished.

Variables work differently in computer science:

- You can create them whenever you want. In fact, you already made one. Remember typing

number = 5above? You made a variable called “number” and set its value to 5. This is called declaring a variable. - In computer science, you get to decide what value variables have, and you can change them whenever you want. This is called assigning values to variables. Try this:

>>> name = "Willie"

>>> "my name is " + name

- You can call them whatever you want (no spaces though!) In math, variables have names like

x,y, andt. In computer science, we usually call them things likenumber_of_coins_in_my_handordirection_my_character_is_facingbecause it’s less confusing.

You can think about variables as little boxes in your computer’s memory that store things so you can use them later.

Variables in memory

Let’s do some tests to see more about how variables work.

A. Variable tests

Create a new file called lab_02.py in your cs9/unit_00 directory.

(This should be at ~/Desktop/cs9/unit_00/lab_02.py.)

You’ll be turning in this file at the end of the lab. Copy this starter code:

# Unit 0 Lab 2

# Author: Your Name

from turtle import *

# A. VARIABLE TESTS

# variable test 0

name = "Your name"

print()

print("Variable test 0")

print("Hello")

print(name)

#variable test 1

print()

print("Variable test 1")

#variable test 2

print()

print("Variable test 2")

A.0 Variable test 0

💻 Start by replacing "Your name" with your name (but keep the ""). Now you

have declared the name variable and assigned your name as its value.

💻 Save the file and run the program like this:

~/Desktop/cs9/unit_01$ python lab_02.py

Variable test 0

Hello

FyiSi

~/Desktop/cs9/unit_01$

What just happened? After storing your name in the name variable, print(name) prints out whatever

is stored in the variable.

Let’s do another test. 💻 Type the following lines of code so that the variable test 0

section looks like this:

# variable test 0

name = "Your name"

print()

print("Variable test 0")

print("Hello")

print(name)

name = "Friend's name"

print("Hello")

print(name)

💻 Replace "Friend's name" with your friend’s name.

Now our program is printing the name variable twice but we’ve assigned different values to the

variable at different places in the code. What do you think will happen?

💻 Run the code to find out:

~/Desktop/cs9/unit_01$ python lab_02.py

Variable test 0

Hello

FyiSi

Hello

cs9

~/Desktop/cs9/unit_01$

Is this the output you expected? Talk with your group about what happened when you assigned the

name variable twice.

A.1 Variable test 1

💻 Type the following lines of code under the variable test 1 section of your program.

Replace "color" and "fruit" with your favorite color and fruit:

# variable test 1

print()

print("Variable test 1")

favorite_color = "color"

print("Your favorite color is " + favorite_color)

print("Your favorite fruit is " + favorite_fruit)

favorite_fruit = "fruit"

💻 Try running the program now with python lab_02.py

Hmm, something is wrong here. Work with your group to find and fix the bug.

A.2 Variable test 2

💻 Type the following lines in the variable test 2 section of your program:

# variable test 2

print()

print("Variable test 2")

favorite_artist = input("What is your favorite artist? ")

print("Oh, I love " + favorite_artist + "!")

💻 Run your program multiple times and change up what artist you type.

This shows how your programs can be responsive to user input and how you can store information from the user in variables that may change every time your program runs.

👾 💬 FYI

You can get input from the user while your program is running using

input(PROMPT).If you want to get a number from the user, use

int(input("PROMPT")). This is because Python treats numbers and words differently. We’ll talk more about this next unit.

✅ CHECKPOINT:

Answer the following check-in questions on your group’s Google doc before moving on:

- What is a variable?

- How do you declare a variable?

- At what point in a program can you use a variable?

Loops

In Python, when you want to run the same code multiple times, we use loops. If you have used Scratch before, you have seen loops before:

Scratch loop

How does a loop work in python? Let’s see.

💻 Copy and paste the following code into your lab_02.py file:

# B. Calculations

# YOUR CODE FOR HERE (B)

# C. Geometric sequences

# YOUR CODE FOR HERE (C)

# D. Fibonacci

# YOUR CODE FOR HERE (D)

# E. Loopy drawings

# YOUR CODE FOR HERE (E)

# F. Variable drawings

# YOUR CODE FOR HERE (E)

# G. Drawing Fibonacci

# YOUR CODE FOR HERE (G)

Do these and check with your group if you get stuck:

B. Calculations

Let’s start by performing some calculations for many numbers.

💻 Type this starter code at YOUR CODE HERE (B).

# B. Calculations

for i in range(10):

print(i)

B.0 Listing numbers

💻 Run your program and see what gets output.

This loop runs 10 times, repeating everything indented to the right of the for i in range(10): line.

i is a variable that gets incremented by one every time the loop runs.

B.1 Listing more numbers

💻 Edit the code to make the loop run a different number of times, maybe 5 or 14. Can you figure out how to do it?

Notice that the count inside i starts at 0 and goes up to the number inside range() but

doesn’t include that number.

B.2 Squaring numbers

💻 Finally, edit the code to make the loop print out the square of every number from 0 to 12. When you run your program, the output should look like this:

$ python lab_02.py

0

1

4

9

16

25

36

49

64

81

100

121

👾 💬 FYI

If you don’t want code to be executed when you run a program, you can comment it out by placing

#at the beginning of the line.If you don’t wan’t to run the code you wrote in the first part of the lab, just comment it out.

C. Geometric sequences

Loops are particularly useful when we need to do things over time. To see this, let’s use a loop to list out the first 10 terms in a geometric sequence.

👾 💬 FYI

Sequences are ordered collections of numbers that have a pattern to determine which numbers appear in the sequence. For example,

2, 4, 6, 8, 10,...is a sequence where each number 2 more than the previous number.Geometric sequences are sequences where there is a common ratio between each number in the sequence. For example,

3, 9, 27, 81,...is a geometric sequence where each number is 3 times the number before it (making the common ratio 3).

💻 Type this code at YOUR CODE HERE (C).

# C. Geometric sequences

ratio = float(input("What should the ratio of the sequence be? "))

curr = 1

print(curr)

C.0 Pseudocode

✏️ To get started, think through the pseudo-code of what we want this program to do. Pseudocode is an outline of the program we’ll ultimately write where we don’t worry about using Python syntax.

Here are some things to consider:

- You will use a loop to calculate each term in the sequence. What is the formula you will use at each step in the loop to calculate the term?

- You will need to know the previous term to calculate the current term. How will you keep track of this?

C.1 Code

After you are confident your pseduocode has the correct logic, translate it into

python code. Type this code below the existing code in the C. Sequences section.

D. Fibonacci

Let’s explore another sequence, the Fibonacci sequence. This sequence has all kinds of interesting properties.

👀 Watch this video about how the Fibonacci sequence appears in nature:

We’re going to write an algorithm to print out numbers in the Fibonnaci sequence.

💻 Type this code at YOUR CODE HERE (D).

# D. Fibonacci

num_terms = int(input("How many terms of the fibonacci sequence should I display? "))

D.0 Pseudocode

✏️ Just like you did with the geometric series algorithm, think through the pseudo-code of what we want the Fibonacci sequence algorithm to do.

Here are some things to consider:

- Your algorithm should print out the number of terms inputed by the user and

stored in

num_terms. - Just like before, you will need a way to track the previous terms of the sequence, but this time you need two past terms instead of just one.

D.1 Code

💻 After you are confident your pseduocode has the correct logic, translate it into

python code. Type this code below the existing code in the D. Fibonacci section.

✅ CHECKPOINT:

Answer the following check-in questions on your group’s Google doc before moving on:

- What is a loop?

- How do you put code into a loop?

- What changes over each iteration of a loop? What stays the same?

E. Loopy drawings

Loops are not just useful for numbers and sequences, they can also be helpful in making drawings. Any time your code does the same thing multiple times, you can use a loop to make it simplier and more powerful.

Take a look at the code we’ve been using to draw a square:

forward(100)

right(90)

forward(100)

right(90)

forward(100)

right(90)

forward(100)

right(90)

Pretty repetitive, right?

💻 Edit this code to use a loop to avoid repeating the same code over and over

again. Type this code at YOUR CODE HERE (E).

F. Variable drawings

Loops are even more powerful drawing tools when paired with variables. This allows us to draw things differently over time or based on user input.

💻 Type this code at YOUR CODE HERE (F).

# F. Variable drawings

num_sides = int(input("How many sides? "))

💻 Write a loop that draws a polygon with the number of sides

stored in num_sides. Type this code below the existing code in the

F. Variable Drawing section.

G. Drawing Fibonacci

Finally, let’s use the code you wrote to calculate Fibonacci sequences to make pattern drawings inspired by flowers and pinecones.

Fibonacci drawing

G.0 One spiral

First, use your Fibonacci code to draw a single spiral. You can do this by drawing a line for each number in the Fibonacci sequence and connecting the lines at a standard angle.

💻 Write this code at YOUR CODE HERE (G).

The Turtle should draw something like this:

Fibonacci spiral

G.1 Multiple spirals

💻 Now, loop your code in G. Drawing Fibonacci to draw multiple spirals originating from the

center.

Now, the Turtle should draw something like this:

Many spirals

👾 💬 FYI

You can return your turtle to the center of the window usinggoto(0, 0). If you want, you can usepenup()andpendown()to keep the turtle from drawing as it returns to the center.

G.2 Clockwise and counterclockwise

To get a pinecone or flower effect like the video above described, you’ll need to spiral clockwise and countercloackwise.

💻 Repeat your spiral code, changing it to make your spirals turn in the other direction.

Deliverables

- Once you’ve reached the end of the lab (or class time is over), please submit the

lab_02.pyfile you have been creating - Each member of your group should submit their own file.

- You will get credit even if you don’t finish parts A-G.